IS A STORM BREWING IN THE BANKSY TRADE MARK TEACUP?

Posted on: October 7, 2020 by Adam Jomeen

Banksy hit the headlines last month when an EU trade mark featuring his iconic Flower Thrower graffiti was struck down by the EU’s Intellectual Property Office, reigniting claims that the Bristolian street artist is abusing trademark law to secure rights against third parties who commercialise his work without consent. Whilst Banksy could in principle take action against unauthorised use of his work under copyright law, a copyright claim would require him to divulge a central tenet of his brand: his identity.

Original application filed in March 2019

As reported last year, a UK greetings card company called Full Colour Black (FCB) filed proceedings to invalidate the Flower Thrower EUTM in March 2019. The mark was registered by Pest Control, Banksy’s principal corporate vehicle, in August 2014. Whilst EU trade marks are vulnerable to revocation if they are not put to “genuine use” within 5 years of registration, FCB filed ahead of the 5th anniversary and argued that the Flower Thrower should be struck down on “absolute” grounds that: (1) As an artwork, the mark is inherently unlikely to function as a trade mark; (2) Even if the mark were inherently distinctive, its reproduction by third parties meant it lacked the requisite “distinctive character” at the date of registration; and (3) Pest Control registered the mark with no intention to put it to genuine use, seeking instead, in bad faith, to restrict reproduction by third parties such as FCB who do not use the mark to identify its goods or to carve-out a portion of the commercial market.

EUIPO decision of 14 September 2020

The EUIPO invalidated the Flower Thrower EUTM on the third ground (bad faith) and did not analyse the other two grounds.

The EUIPO noted that neither Pest Control nor Banksy was producing, selling or providing any goods or services under the Flower Thrower mark prior to filing in 2014 and up to the date of FCB’s application (March 2019). This was supported by extracts from Banksy’s website, allegedly from 2010-11, with statements including: “Banksy has never produced greeting cards, mugs or photo canvases of his work”; “Please take anything from this site and make your own (non-commercial use only thanks)”; and “All images are made available to download for personal amusement only”. Public statements by Banksy and his “self-proclaimed legal advisor” (Mark Stephens) in October 2019 were cited as evidence of bad faith: Banksy conceded that GDP was motivated by “a trademark dispute” and Stephens recommended “that Banksy begin his own range of merchandise and open a shop as a solution to the issue.” The EUIPO held: “by their own words, they admit that the use made of the sign was not genuine trade mark use in order to create or maintain a share of the market by commercialising goods, but only to circumvent the law.”

Stepping back – the decision in context

On one level, the EUIPO decision is something of a storm in a tea cup. Why? Because Pest Control applied for a near identical back-up EUTM featuring the Flower Thrower mark on 30 August 2019 which was registered by the EUIPO on 22 May 2020. FCB objected to the registration, arguing forcefully that Pest Control was seeking to undermine the pending invalidity proceedings and circumvent the risk of its 2014 Flower Thrower EUTM being cancelled. The EUIPO nevertheless proceeded with the registration, forwarding a copy of FCB’s objections to Pest Control and noting: “The observations do not give rise to serious doubts concerning the eligibility of the trade mark for registration.” Through its 2020 EUTM, Pest Control thus enjoys full EU trade mark rights over the Flower Thrower mark notwithstanding the recent EUIPO ruling.

The ruling is also a first instance decision capable of appeal. Pest Control has two months to appeal and, should it do so, two further months to submit written grounds. FCB would have two months to respond to Pest Control’s grounds of appeal and this period can be extended upon request. There is, therefore, scope for this particular proceeding to rumble on for some time.

Notwithstanding these observations, this is the first time the EUIPO has addressed the claims against Banksy and Pest Control and the decision may indicate the direction of travel. This is relevant because the EUIPO is considering five further applications to invalidate EUTMs held by Pest Control featuring the following Banksy artworks:

Pest Control sought registration for each art work in November 2018 and they were registered as EUTMs by the EUIPO in June 2019. FCB filed invalidity applications in November 2019 and the proceedings are at an advanced stage: Pest Control responded in May 2020; FCB submitted further observations in July 2020; and Pest Control’s final submissions are due this month. FCB make the same arguments in these five applications as they made against the Flower Thrower, namely that the EUIPO should invalidate the EUTMs on the grounds that the works fail inherently to function as trademarks; lack distinctive character; and were filed in bad faith.

More questions than answers remain for now. Will the EUIPO extend its Flower Thrower finding and conclude that these five marks were also filed in bad faith? That risk may encourage Pest Control to appeal with a view to disturbing that finding. Or will the EUIPO address the key questions here regarding the ability of Banksy artworks to function as trade marks in the context of their widespread (and largely unchecked) reproduction by third parties? Do they indicate commercial origin, enable Pest Control to carve out a portion of the commercial market and enable consumers to distinguish Pest Control goods from those of other companies? Whether they could in principle, and whether they do in practice, may be different questions.

Banksy’s market – and buyer due diligence

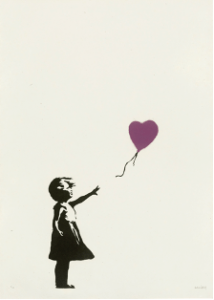

In the meantime, Banksy’s market continues its unabated ascent. His largest known work – Forgive us our Trespassing (2011) – sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for around £6.4m on 6 October 2020 – double its high estimate; Christie’s achieved £791,250 on 23 September 2020 for Balloon Girl – Colour AP (Purple) (2004) – a world record for a Banksy print and a print sold in an online auction; and his 2005 adaptation of Claude Monet’s (1840 – 1926) tranquil scene at Giverny – wryly entitled Show me the Monet – is set to headline Sotheby’s next livestream auction on 21 October 2020 with a £3-5m estimate.

In this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that works acquired from Banksy’s GDP store less than a year ago are beginning to surface at auction. Tate Ward, a recent entrant to the auction market and incorporated in 2018, sold the first Banksquiat print to reach public auction on 28 August 2020 for £118,750. This represents a healthy return on investment: Banksquiat was sold through GDP in two colour ways (black and grey), each in an edition of 300, for just £500.

As COVID moves more sales online and there are fewer opportunities to inspect art works, buyer due diligence has never been more important. GDP’s terms and conditions indicated Banksy’s desire to “sell things to people who want them, rather than people who want to make a profit”. To that end, it provided that Certificates of Authenticity (CoA) would only be issued on the second anniversary of purchase and indicated that buyers may have been required to sign a separate sales agreement as a condition of purchase. The Tate Ward lot description for the Banksquiat sold on 28 August 2020 stated: “Pest Control Certificate Of Authenticity Pending, this will be forwarded to the buyer when received”. This raises questions: Did the seller sign a sales agreement with GDP which would presumably have restricted resale; if so, was sale at public auction in breach; and is the issuance of the CoA by Pest Control in late 2021 contingent on the seller’s compliance with the sales agreement?

Another important question presents itself: Without a CoA, what comfort does a buyer have that the work is, indeed, authentic? This is particularly relevant for recent Banksy prints which have yet to be seen in the flesh (or pigment) by many people — I have yet to see one. Auction houses typically stand behind the works they sell and agree to reimburse the purchase price to buyers where two recognised experts confirm within a set period that the work is not authentic. The devil is, as ever, in the detail: Whereas the terms and conditions of leading houses such as Phillips, Christie’s and Sotheby’s warrant authenticity for 5 years from the date of sale, the Tate Ward warranty lasts just 30 days. A 30-day warranty has no practical value for Banksy’s GDP works, since Pest Control is the only body capable of authenticating these and will not do so until the second anniversary of purchase. The buyer of the Banksquiat on 28 August 2020 is accordingly left without a contractual remedy should the work prove to be inauthentic (although other claims may be available).

Tate Ward’s forthcoming sale of Urban and Contemporary Art on 14 October 2020 offers further GDP works, including a grey Banksquiat (estimate £45,000-£55,000) and a Banksy Thrower triptych featuring the contested Flower Thrower mark (see above). The Banksy Thrower was sold in an edition of 100 for £750 and carries an estimate of £135,000-£165,000. Both works bear the same lot note: “Pest Control Certificate Of Authenticity Pending, this will be forwarded to the buyer when received”.

Images credit: © Banksy, Pest Control Ltd.